Zero Trust security model

06/10/2022What is microsegmentation?

06/10/2022Understanding ransomware

Ransomware is a type of malware that encrypts an organization’s high-value data, such as files, documents and images, and then demands a ransom from the company to restore access to that data. To be successful, the ransomware malware needs to gain access to a target system, encrypt the files there, and demand a ransom from the company. A bitcoin or cryptocurrency ransom would then typically need to be paid to release the encrypted data files.

Once simply a nuisance strain of malware used by cybercriminals to restrict access to files and data through encryption, ransomware has morphed into an attack method of epic proportions. While the threat of permanent data loss alone is jarring, cybercriminals and nation-state hackers have become sophisticated enough to use ransomware to penetrate and cripple large enterprises, federal governments, global infrastructure and healthcare organizations.

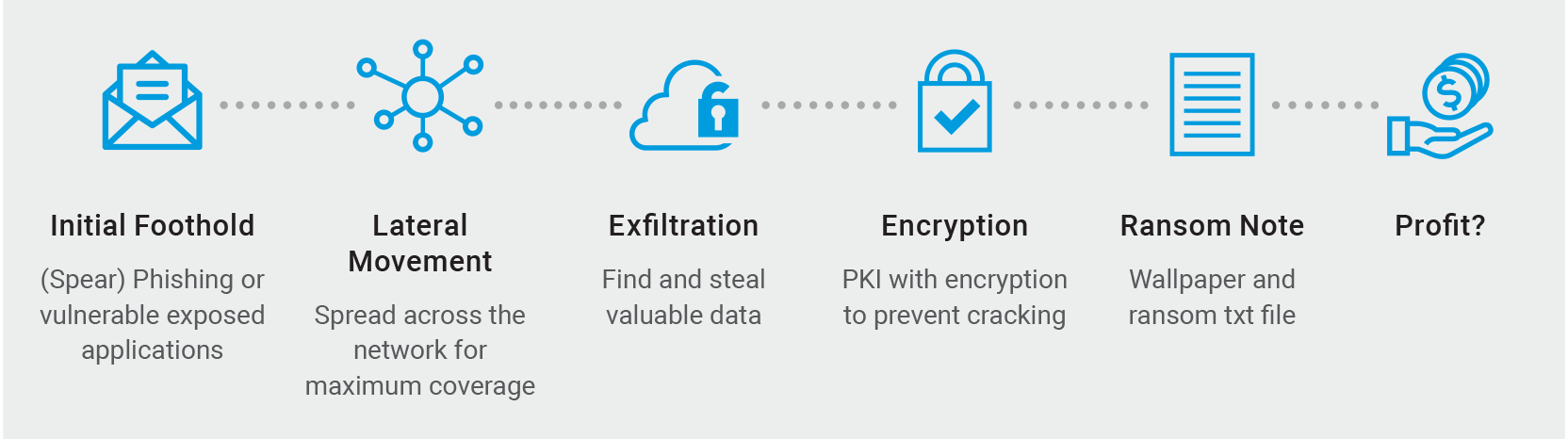

Depicted here is a typical ransomware killchain from Akamai’s Ransomware Threat Report.

What is the impact of ransomware?

In 2020, the Snake ransomware attack brought Honda’s global operations to a standstill. That same week, Snake, a form of file-encrypting malware, also hit South American energy-distribution company Enel Argentina. In 2019, cybercriminals encrypted files that froze the computer networks of Pemex, Mexico’s state-owned gas and oil conglomerate, demanding $5 million to restore service. And in 2017, the WannaCry cryptoworm hit 230,000 computers globally by exploiting a vulnerability in Microsoft Windows.

Today, through a mix of outdated technology, “good enough” defense strategies focused solely on perimeters and endpoints, lack of training (and poor security etiquette), and no known “silver bullet” solution, organizations of all sizes are at risk. Especially as cybercriminals are making it their business to encrypt as many computer systems on the corporate network as possible in order to extort a ransom ranging from thousands to millions of dollars. In fact, ransomware attacks were predicted to occur every 11 seconds in 2021 at a global cost of $20 billion.

Ransomware Threat Report

The Akamai Ransomware Threat Report will focus on organizations that execute cybersecurity attacks, and the ways in which they operate.

How does ransomware spread?

A popular method to introduce ransomware to a new environment is through the use of phishing or phishing emails. A malicious email or email attachment may contain a link to a website that hosts a malware download or an attachment with a built-in downloader. If the email recipient opens the phishing email, then the ransomware is downloaded and executed on their computer instantly.

Once an endpoint or victim’s computer is infected, the cyberattack will attempt to spread to as many machines as possible throughout the network by executing unauthorized lateral movement to maximize the blast radius (encrypting as many disks as possible).

Another popular ransomware infection vector takes advantage of Remote Desktop Protocols (RDPs). With RDP, a hacker who has gained access to login credentials can use them to authenticate and remotely access endpoints within an enterprise network. With this access, bad actors can directly download and execute the malware on machines under their control and attempt to move laterally through the environment, capturing and encrypting data on additional assets.

The encryption of a user’s files is the unique aspect of a ransomware attack. By encrypting highly valuable data, the cybercriminals or ransomware attacker can demand a ransom in exchange for the decryptor or decryption keys to release the files back to the company. However, ransomware hackers don’t always release the encrypted files back to the organization, even if they pay the ransom.

Why do legacy firewalls fail when attempting protection against ransomware?

Legacy firewalls control communications between VLANs and zones. However, legacy firewalls don’t allow you to block traffic inside the VLAN, so this approach is ineffective when you want to prevent propagation within a segment. This is due to different network architecture limitations with the existing legacy firewall model. Once an attacker has compromised a machine on a single VLAN, they will eventually compromise another machine on the same VLAN and use it to leapfrog to other assets in the data center, including backup servers.

How to detect and block ransomware threats

As a defender, you want to limit access between machines as much as possible to prevent lateral movement. Specifically around the protocols and services ransomware campaigns often exploit. There is no reason for employees’ laptops to communicate with one another and no reason for domain members to connect over SMB.

Our solutions allow the defender to limit traffic between any two machines. Because the platform uses a software-based segmentation approach, you can create policies that block communication between laptops or limit SMB traffic between domain members and allow them only to access specific servers like the domain controller.

Additionally, Akamai provides visibility, down to the process level, of communications and dependencies between your assets. This enables you to assess risk ahead of time and develop proactive strategies for protecting critical assets and high-risk components such as backups.

The platform also comes with robust threat detection capabilities, so you can look for communication with known malicious domains or the presence of known malicious processes in your environment that may indicate a malware breach.

5-Step Ransomware Defense Ebook

Discover how to strengthen your defenses beyond the perimeter.

What should I do if I’m attacked by ransomware?

Because ransomware relies on lateral movement to execute a successful attack, that’s where organizations should focus their effort. If you determine that an active ransomware attack is in progress, use tools that provide visibility to understand the breach’s scope. Based on what you learn, you can then isolate affected parts of the network from the rest of the organization and add more security layers to critical applications and backups. Only once you have taken mitigation steps and restored services should you gradually re-enable communication flows.

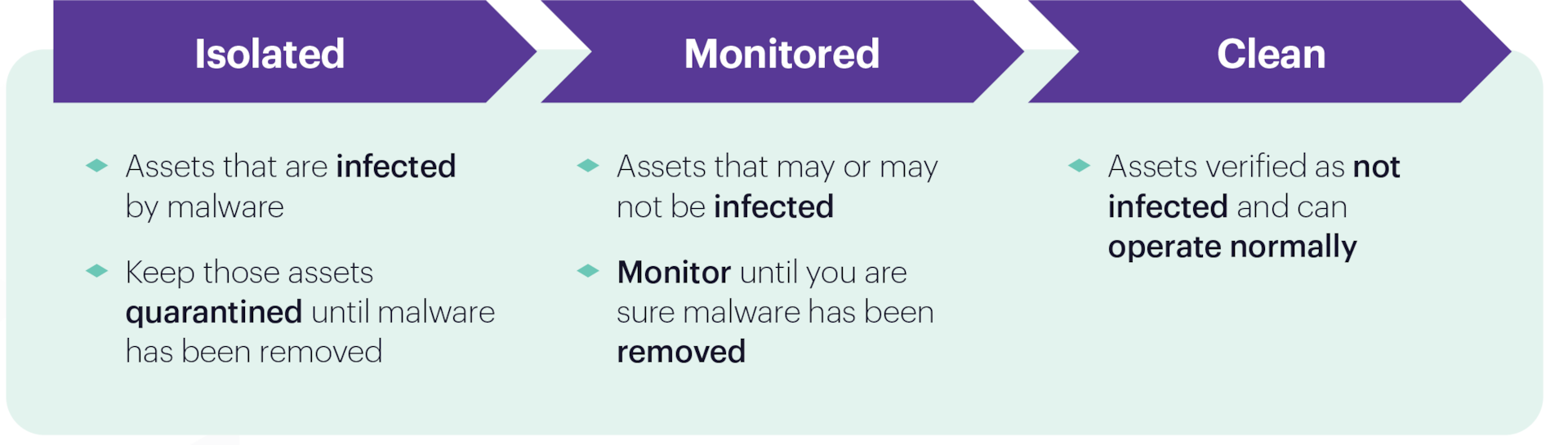

Once you have a list of all infected machines and IOCs (indicators of compromise), you can start disinfecting. Divide your machines into three label groups: Isolated, Monitored and Clean.

Depicted here is the recommended recovery process from the Akamai white paper: Risk Mitigation, Prevention and Cutting the Kill Chain — Stop the Impact of Ransomware.

Additionally, alerting law-enforcement agencies (such as the FBI) about the incident could facilitate an investigation and eventual prosecution against the cybercrime.

How does crypto ransomware work?

A ransomware attack begins with an initial breach, often enabled by social engineering, a phishing email, malicious email attachment or vulnerabilities in the network perimeter. The malware will start to move through your network and attempt to maximize damage from its landing point. Typically, bad actors seek to seize control of a domain controller, compromise credentials and locate and encrypt any data backups in place to prevent operators from restoring infected and frozen services.

How do you find out what ransomware you have?

There are many different variants of ransomware. However, looking at the specific IOCs based on suspicious domain names, IP addresses and file hashes associated with known malicious activity can help you learn more about the attack’s origin and how to respond.

Stop the Impact of Ransomware White Paper

Protect your enterprise and contain the lateral movement in your network.

What are the most common forms of ransomware?

Some campaigns are highly targeted advanced, persistent threats (APTs) run by a bad actor, while others are opportunistic, typically executed by scripts. However, there are two main categories. Attacks that encrypt files and hold them for ransom payments are known as crypto-ransomware, and ransomware that prevents users from accessing a device is known as locker ransomware.

New types of ransomware, malicious code, malicious software, malicious attachments, scareware, and other new ransomware variants are appearing frequently in the wild. There are even documented cases of paid ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS), an example being REvil (Ransomware Evil; also known as Sodinokibi) which was a Russia-based or Russian-speaking private RaaS.

How did ransomware get started?

If we look back to just a few years ago, most ransomware attacks were using malvertising as their initial penetration vector targeting pretty much anyone who would load these malicious ads, be it “Bob from accounting” in a large corporation or someone’s grandmother trying to read her emails. Ransomware did not really distinguish between who it was targeting – it targeted everyone and if these victims paid – great – and if they didn’t it was fine because there were plenty of other fish in the sea.

However, this all changed in 2012 with Shamoon, a targeted Iranian cyberattack against the Saudi Aramco corporation. Shamoon allowed the attackers to exfiltrate large quantities of information out of Aramco and once the exfiltration was done, the attackers used Shamoon to overwrite the master boot record in the attacked machines, rendering them useless until they were reinstalled. This loss of functionality caused a substantial amount of downtime for the company.

Locky was ransomware malware released in 2016. It is delivered by email (that is allegedly an invoice requiring payment) with an attached Microsoft Word document that contains malicious macros. When the user opens the document, it appears to be full of gibberish, and includes the phrase “Enable macro if data encoding is incorrect,” a social engineering technique.

Petya is a family of encrypting malware that was first discovered in 2016. The malware targets Microsoft Windows–based systems, infecting the master boot record to execute a payload that encrypts a hard drive’s file system table and prevents Windows from booting. It subsequently demands that the user make a payment in bitcoin in order to regain access to the system.

How did ransomware evolve?

Fast forward to 2017. WannaCry and NotPetya, two devastating ransomware attacks, wreaked havoc on large corporations and government entities. The unique thing about these attacks, other than showing how fragile the internet is, was that these attacks used zero-day vulnerabilities to move laterally between computers on the network in a virulent way, infecting and rendering every machine it encountered completely useless. A lot was written about NotPetya and WannaCry, but we know today that the motives behind these attacks were related to cyberattacks initiated by a nation-state adversary.

These ransomware attacks then started being used by crimeware groups, which until that point were mostly focused on using malware like Zeus (and all of its variants) to breach people’s bank accounts to siphon money. This was often a long, complicated, and risky operation – especially when it came to actually receiving the money. Until now, the prevailing belief was just that it could be easier to target only large corporations and blackmail them into sending large amounts of money in bitcoin, which made ransomware more of a corporate threat that needs to worry CISOs, but not necessarily unsuspecting private citizens.

Ryuk is the name of a ransomware family, first discovered in the wild in August 2018. Named after a fictional character in a popular Japanese comic book and cartoon series, it is now known as one of the nastiest ransomware families to ever plague systems worldwide.

Now jump to 2020. While the COVID-19 pandemic rages on around the world and most people are forced into working from home, completely changing threat models, risk factors and network architectures on very short notice, the world started seeing ransomware attack operators change their modus operandi. They were now targeting large companies by conducting a double extortion attack, where the attackers not only breach the organization, encrypt the files and hold them as hostage — but they also started exfiltrating that precious and highly valuable data back to the attackers, threatening to make this data publicly available if the ransom is not paid.

Executive order promotes segmentation for slowing ransomware

In 2021 a U.S. White House memo discussing the growth of ransomware attacks, the topic of the often overlooked importance of network segmentation was highlighted, alongside the more traditional precautions and recommendations such as patching, 2FA and updated security products.

Network segmentation helps not only to mitigate the risk in some cases, but also to significantly lower the risk of a double extortion attack if implemented properly, by containing and minimizing the “blast radius” of a ransomware attack. Even if antivirus software and EDRs failed to prevent the ransomware from executing, proper segmentation will keep that damage contained and won’t allow the attackers to move laterally across the network to steal more sensitive data and encrypt more machines.

The granularity of segmenting a network with Akamai’s unique software approach allows you to create “network silos” between servers, applications, different operating systems, cloud instances and so on. The strength of lowering ransomware risk by using a proper segmentation policy comes from its simplicity — a bit can either travel on the wire (or a Vswitch) to a different machine (or a VM/container) or it can be blocked, rendering the attackers’ attempt to reach more resources on the network useless, giving the blue team more time to respond to the attack and update the key stakeholders in the organization so they can make informed decisions about the damage of said attack.

Network segmentation is not an alternative to an antivirus, antimalware or an EDR platform, it is a supplemental approach that has proven to significantly reduce, if not to completely eliminate the risk of large scale lateral movement based attacks across organizations.

How do you combat the ransomware threat?

This new age of ransomware attacks shines a light on a problem that has been long overdue from solving: lateral movement.

In order for the attackers to exfiltrate all of that data, they have to know where it is on the network — and in order to know that, they have to map the network and know it just as good (if not better) than the people who had originally built it. This requires the attackers to “move laterally” from one machine/server to another, often using different credentials by stealing them from various machines across the network.

Many security vendors tried to solve this problem, and some succeeded more than others. The security market has seen new types of products emerge over the years to prevent this very problem – from DLP solutions to EDRs and EPPs – they all have tried but had very partial success in solving the problem of lateral movement.

Solving lateral movement is hard — attackers are using the features of a network against itself.

They will use administrator credentials and various legitimate administrative tools (such as Microsoft’s own Psexec or Remote Desktop, or even WMI) moving from machine to machine, executing malicious commands and payloads in order to steal data and later encrypt the network and start the extortion operation. Many organizations are investing resources in trying to put a Band-Aid on this problem by overly monitoring various resources using EDR/EPP products that weren’t meant to be used for that purpose, thus resulting in partial success of mitigating or even lowering the risk of a ransomware attack.

Halting lateral movement with segmentation

However, there is a solution and it’s much simpler to implement than you may think — network segmentation. Segmentation is something that’s often forgotten or even ignored altogether since it’s believed to be hard to implement, and requires careful attention to network engineering and asset management. Because of this, network segmentation is often disregarded, which leaves networks “flat,” meaning every endpoint or server can talk to each other without any restriction.

Until recently, segmenting a network meant putting different assets in different subnets with a firewall in the middle. This didn’t allow any granularity, made managing the network significantly harder, and required administrators to manage complex firewall configurations along with managing IP address allocations on different subnets, which then made designing and scaling the network much harder for the IT staff, while incorrect configurations could lead to either a security risk or a network failure (and, in some cases, even to both!). This, again, caused IT staff to not put an emphasis on segmentation and put much more trust on execution prevention products while leaving the network completely flat and unsegmented.